- Insights This article was written by a TIA community member. Insights pieces undergo the same rigorous editorial process that newsroom-produced articles have.

This ecommerce startup uses direct-to-consumer model to sell healthy products in Malaysia

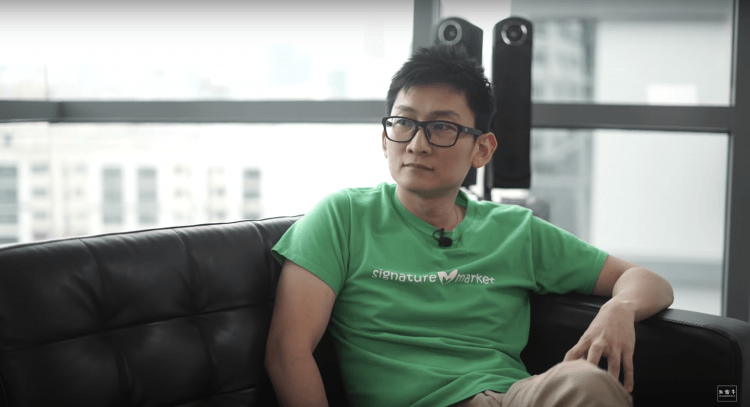

Edwin Wang, co-founder of Signature Market

This article is part of Tech in Asia’s partnership with 米雷牛 Millennials where we publish the revised transcripts from their interviews with millennial entrepreneurs. This is heavily revised from the original transcript of the interview. For the full interview, go here.

Edwin Wang is the co-founder of Signature Market, a Malaysia-based direct-to-consumer ecommerce brand for healthy and organic products. Wang is a second-time startup founder and has been in the ecommerce industry for more than 20 years. He scaled his first company, Everyday.com.my, to an annual revenue of RM50 million (or ~US$12.3 million) before it was acquired by LivingSocial.

Wang and I talk about the problem Signature Market is trying to address, the state of the FMCG industry in Malaysia, and the potential of the direct-to-consumer model.

What is the problem that FMCG consumers are facing now?

When people became aware that a lot of mainstream products were not actually healthy, they began to ask, “What options do I have now?”

Previously, a lot of consumers actually did not know that many of the packaged food products that they had been buying were actually fake food (i.e. with preservatives and minimal natural ingredients). For example, an orange juice product’s label says that it’s made from fresh oranges, but it doesn’t say that it also has a lot of chemicals in it. So, consumers are misinformed.

But a lot of people are choosing real food now vs what the FMCG giants are offering.

What are the changes in the FMCG industry?

The industry is huge, but the big ones are losing market share. A lot of smaller brands, which are more flexible and innovative, are giving consumers what they want. They usually start from bazaars, are ethical, and don’t put preservatives in their food.

They also use the direct-to-consumer model, which allows them to closely interact with and understand the consumers more. It also enables them to adapt to change much faster because the communication is very direct.

What is the difference between the direct-to-consumer model and the traditional one?

Let’s take my company as an example. Our method is very different from traditional companies in that we are more lean and startup-like. So, it only takes us three to six weeks to launch a new product. When we test products, we can also know in just three months whether they’re going to be bestsellers.

The giants, on the other hand, have to produce a lot of products, put them in all the distribution channels, and engage in a lot of marketing campaigns just to launch a product. For them, every single launch is important, and every single product is a business model in itself.

What kind of data do you look at?

We look at two metrics. The first one is: How do we get consumers to impulsively buy from us for the first time? How fast is that decision?

The second one is the return. How many customers will like their first experience with us and return to purchase again? This will make us a sustainable business.

But in the packaged consumer goods industry, there are a lot of factors (e.g. price, product weight, etc.) that affect a consumer’s purchase decision. It’s a guessing game, and we can play around this more.

What is the biggest challenge of using the direct-to-consumer model?

It’s still very new, even in the US. There are many success stories, but there aren’t a lot of players in our space who have a good history.

In our case, we’re still innovating on our own. We’re trying to figure out how to make this better, so there’s a lot of testing and, consequently, uncertainty involved.

Challenges are always there for startups—cash flow is always the most critical problem for us. But I think we are actually creating value in the industry in a lot of aspects as we do differently from the giants.

Do you hope to see more players using this model?

Having more players is better because it gives consumers better choices. The packaged consumer goods industry in Malaysia alone is worth US$14 billion, so there’s a lot of opportunities.

Our vision is about getting consumers to be healthier. But if there’s only one or two players in the industry, then we’re still very far from our goal.

Another thing is with more players in the industry, innovation will also be so much greater. Malaysia’s food industry is pretty advanced already, but I hope we can become like Australia. When people think of healthy products, they think of Malaysia.

To help the ecosystem, we share our statistics with food producers—what are the bestsellers, what kinds of price points work, etc. Some players have the products but they lack marketing skills. They do not know how to reach customers. So, we take them in, put their food under our branding, and share some data with them. If they improve, we also improve.

Converted from Malaysian ringgit. US$1 = RM4.08.

The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of Tech in Asia.

Recommended reads

Temu’s logistics power play puts Shein on the defensive in the US

Temu’s logistics power play puts Shein on the defensive in the US Quick meals, high costs: inside India’s 10-minute food fight

Quick meals, high costs: inside India’s 10-minute food fight Zimplistic flips to a profit in 2021 after troubles

Zimplistic flips to a profit in 2021 after troubles 10 predictions for SEA’s healthtech in 2023

10 predictions for SEA’s healthtech in 2023 Cold chain may be the next opportunity for Indonesia’s logistics startups

Cold chain may be the next opportunity for Indonesia’s logistics startups How to stop your startup becoming a ‘franken-org’

How to stop your startup becoming a ‘franken-org’ Oddle built a profitable food delivery business. Here’s how

Oddle built a profitable food delivery business. Here’s how Velocity Ventures invests in Israeli robot kitchen firm

Velocity Ventures invests in Israeli robot kitchen firm Recession Run: Wavemaker’s Santos sees a crisis as a flight to quality

Recession Run: Wavemaker’s Santos sees a crisis as a flight to quality East Ventures pours seed funding into Indonesian online kitchen startup

East Ventures pours seed funding into Indonesian online kitchen startup

Editing by Charmaine de Lazo

(And yes, we’re serious about ethics and transparency. More information here.)